Private health insurance plans in 2017 paid more than twice what Medicare would have for those same health care services, says a sweeping new study from Rand Corp., a respected research organization.

(KHN Illustration/Getty Images)

Its study, which examines payment rates by private insurers in 25 states to 1,600 hospitals, shines light into a black box of the health industry: what hospitals and other medical providers charge. It is among the first studies to examine on such a wide level just how much more privately insured people pay for health care.

The finding: a whole lot. The difference varies dramatically across the country. And as national health expenses climb, this growing gap poses a serious challenge for lawmakers. The Rand data suggests a need for market changes, which could come in the form of changes in industry behavior or government regulation, in order to bring down hospital prices in the private sector. “If we want to reduce health care spending,” said Christopher Whaley, a Rand economist and one of the paper’s two authors, “we have to do something about higher hospital prices.”

Put another way, if, between 2015 and 2017, hospitals would have charged these health plans the same rates as Medicare, it would have reduced health spending by $7.7 billion.

The national discrepancy is staggering on its own. But the data fluctuated even more when examined on a state-by-state level.

In Indiana, private health plans paid on average more than three times what Medicare did. In Michigan, the most efficient of the states studied, the factor is closer to 1.5 — the result, the study authors said, of uniquely strong negotiating of the powerful UAW union, historically made up of autoworkers.

The difference between Medicare and private coverage rates matters substantially for the approximately 156 million Americans under age 65 who get insurance through work-sponsored health plans, researchers said. For them, higher hospital prices aren’t an abstraction. Those charges ultimately translate to individuals paying more for medical services or monthly premiums.

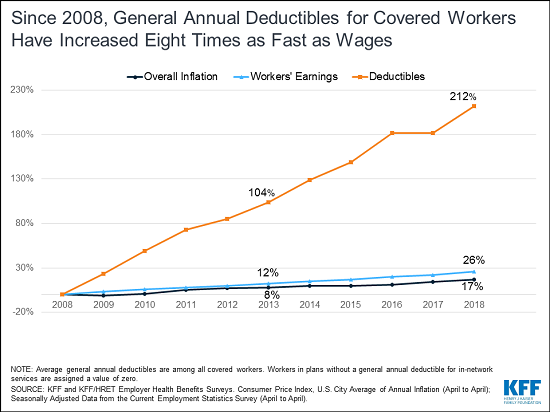

That’s especially true for the increasing number of people who are covered by “high-deductible” health plans and have to pay more of their health care costs out-of-pocket, said Paul Ginsburg, director of the USC-Brookings Schaeffer Initiative for Health Policy. He was not associated with this study.

The gap between Medicare and private plans — and how it plays out across the country — underscores a key point in how American health care is priced. Often, it has little to do with what it costs hospitals or doctors to provide medical care.

“It’s about how much they can charge, how much the market can take,” said Ge Bai, an associate professor at the Johns Hopkins University Carey Business School who studies hospital prices but was not affiliated with the study.

The paper’s authors suggest that publishing this pricing data — which they collected from state databases, health plans and self-insured employers — could empower employers to demand lower prices, effectively correcting how the market functions.

But, they acknowledged, there’s no guarantee that would, in fact, yield better prices.

One issue is that individual hospitals or health systems often have sizable influence in a particular community or state, especially if they are the area’s main health care provider. Another factor: If they are the only facility in the market area to offer a particularly complex service, like neonatal intensive care or specialized cardiac care, they have an upper hand in negotiating the price tag. In those situations, even if an employer is made aware that Medicare pays less, it doesn’t necessarily have the ability to negotiate a lower price.

“Employers and health plans in a lot of cases are really at the mercy of big, must-have systems. If you can’t legitimately threaten to cut a provider or system out of the network, it’s game over,” said Chapin White, a Rand policy researcher and Whaley’s co-author. “That’s when you come up against the limits of market-based approach.”

It wasn’t always this way, said Gerard Anderson, a Johns Hopkins health policy professor and expert in hospital pricing, who was also not involved with the study. Anderson began comparing Medicare prices to that of private insurance in the 1990s, when they paid virtually the same amount for individual services.

Since then, private health plans have lost the ability to negotiate at that same level, in part because many hospital systems have merged, giving the hospitals greater leverage. “Most large, self-insured corporations do not have the market power in their communities to take on the hospitals even if they wanted to do so,” Anderson said.

The RAND findings come as Democrats campaigning for 2020 are reopening the health care reform debate. Single-payer advocates argue, among other points, that covering everyone through a Medicare-like system could bring lower prices and increase efficiency to the rest of the country, or at least give the government leverage to negotiate a better price.

That’s certainly possible, but it isn’t guaranteed. Under single-payer, Anderson said, the challenge would be to make sure Medicare doesn’t simply end up paying more, or that cuts aren’t so dramatic that hospitals and doctors go out of business.

And there’s the political calculus, Ginsburg of Brookings noted. Hospitals, doctors and other health care industries are all influential lobbies and could successfully ward off any efforts to lower prices.

“It’s one thing to have regulatory control of prices. It’s another to set them low enough to make a difference,” he said.

Other strategies, such as a “public option” — which would allow people to opt into a government-provided plan but preserve multiple health care payers — could also make a difference, he said. Lawmakers on the state or federal level could limit what hospitals are allowed to charge for certain medical services, as Maryland does.

Some states have taken smaller-scale approaches, too, by tying their payment rates to a percentage of Medicare, rather than negotiating case by case. In Montana, state employees get coverage that pays about 230% of the Medicare rate on average — an arrangement that saved the state more than $15 million over two years.

For its part, the American Hospital Association, an industry trade group, points to the importance of lowering the cost of prescription drugs or reducing overuse, among other things.

Policy fixes are debatable, White said. But the data makes one point clear: From an efficiency standpoint, the current system isn’t working.

“There are right now the secret negotiations between health plans and hospitals,” and the system is “dysfunctional,” he said.

Original post written by Shefali Luthra at Kaiser Health News